Songs of Ourselves Revision Guide: Improving Your Poetry Analysis

Songs of Ourselves Revision: Close Analysis, Themes and More

Improving Your Songs of Ourselves Analysis:

Close analysis is crucial to the whole of your English GCSE, especially when tackling the poetry paper. Equally, students often find poetry the most intimidating to interpret and analyse because meanings are less obvious and you also have to think about how the words are structured on the page.

In this Songs of Ourselves Revision Guide, you’ll learn how to hone your poetry analysis skills using the “Songs of Ourselves” anthology as a focus. Breaking down literary features and explaining how to engage with form and structure in your analysis, this guide will build your confidence for the GCSE exam. It also includes detailed Songs of Ourselves analysis, including a full set of notes on Maya Angelou’s ‘Caged Bird’ from the Songs of Ourselves anthology and a set of example questions so you can go away and practise your Songs of Ourselves analysis.

Songs of Ourselves Revision Guide: Different Approaches

Thematic: Thematic analysis means looking at how different words used in a poem relate to each other. If the poet uses a lot of words about plants, for example, we could talk about there being a semantic field of botany. These are easy to spot as often the poet is using lots of synonyms to express the same thing.

In ‘Little boy crying’ by Mervyn Morris, Morris switches perspective in the second stanza, offering a glimpse of the little boy’s point of view. This shift reveals how the child perceives his father: instead of an admonishing father, he is a monster from a fairy tale: the “ogre towers above you, that grim giant”, a “colossal cruel” (Allusion to Grimm’s fairytales: Jack and the beanstalk etc). The repetition of these images emphasise the father’s disproportionate size and his cruelty.

Spotting Literary Techniques: There are many different types of literary techniques you will have learned to recognise over the course of your English GCSE studies that you can now apply to your Songs of Ourselves analysis. If you haven’t already, it’s great to make a glossary of some of these key terms (e.g. personification, juxtaposition, onomatopoeia, alliteration) so you know how to recognise and write about them.

Juxtaposition: when two things are placed together to create contrast

‘Amends’ by Adrienne Rich: The enduring conflict between humans and the earth is borne out in the poem’s structural pattern: from the natural imagery of “apple-bough”, “bark”, “ground”, “stones”, “surf”, “sand”, and “cliffs in the first half”, to the man-made “quarry”, “hangared fuselage”, and “trailers” in the second half. The juxtaposition of the natural with the industrial represents the conflict between the two.

Onomatopeia: when a word sounds like what it is

‘Little boy crying’ by Mervyn Morris: “The last words of the first stanza express “the quick slap struck”. The sibilance and onomatopoeia of of the “slap struck” emphasise the graphic physical impact of the slap.”

Alliteration: when the same letter is repeated in adjacent or nearby words

‘Plenty’ by Isobel Dixon: “The alliteration of “d” in the phrase “drought where dams leaked dry,” emphasises the desperation of the family’s situation by drawing increased attention to “drought" and “dry”—“dams” should be full, rather than empty and arid.”

Assonance: the repetition of (generally stressed) vowel sounds in nearby words

‘Muliebrity’ by Sujata Bhatt:

The circularity of memory, and how it works via echoes and dynamic connections, is mirrored in the poet’s frequent use of assonance: “the way she moved her waist”; “cow-dung and road-dust”; “monkey breath and freshly washed clothes”. These aural blends evoke how memories bleed into one another, setting off chains off associations

Caesura: a pause, often in the middle of a line of poetry where it is marked by punctuation.

‘Marrysong’ by Dennis Scott: In lines 7 and 8, we get 4 sentences in 2 lines: “He charted. She made wilderness again./ Roads disappeared. The map was never true.” With so many sentences in so few lines, resulting in multiple caesurae, these lines are stop-start, jerky, and disjointed, once again reflecting the poem's confusion and unpredictability.

Note how in this Songs of Ourselves analysis we have always provided an explanation of the effect of the labelled feature. You can use the PPE: point, evidence, explanation structure to ensure you do this in your close analysis. Analysing poetry isn’t a tick box exercise where you gain marks for spotting a literary technique or feature. You need to think about how this analysis fits into the overarching argument of your essay and your understanding of the poem from the Songs of Ourselves anthology.

Also, make sure you think about what effect each feature may be having on the specific moment you are quoting. While sometimes certain literary features can have similar effects, like an onomatopoeia can immerse us in the sound landscape of a poem, and juxtaposition emphasises contrast, don’t just assume! Think about the poem as a whole too and how the line you’re analysing fits into it.

Improving your Songs of Ourselves Analysis: Structure, Form and Metre

Structure, form and metre often intimidate students but in order to improve your close analysis skills it’s important to understand them and how to write about them. So let’s start by breaking down what each of these terms means:

Form: Form is the structure and shape of the poem. Some poems have set forms. These are inherited “templates” that a poem must fit. A sonnet, for example, is a set form: a Shakespearean sonnet must be 14 lines and follow the rhyme scheme ABAB CDCD EFEF GG. A Haiku is a form; it must be 17 syllables and three lines, arranged 5, 7, 5. Free verse is also a form, when a poem doesn’t obey any particular structure or rhyme scheme.

What different forms can you find in the Songs of Ourselves Anthology?

Metre: Metre is the pattern of how stress falls in a poem. Some forms have a strict metre. Shakespeare’s plays are generally written in iambic pentameter which consists of lines of 10 syllables in an alternating pattern of unstressed/stressed, said to naturally mimic English speech. Think about which words are stressed in the poem you’re looking at, whether there’s a pattern and whether stress falls on any particularly relevant words.

Example Songs of Ourselves Analysis of Structure:

“‘Sonnet 29’ is a Shakespearean sonnet. This is a traditional form for a love poem, following the traditional ABAB CDCD EFEF GG rhyme scheme in three quatrains and a final rhyming couplet. While it is written in iambic pentameter, this rhythm is broken in a number of places, leading to a sense of uneasiness and uncertainty—appropriate for a poem about the trials, failures, and endings of romantic relationships. Millay uses a traditional form to express views on modern love and life.”

This might seem a bit complicated but there are lots of straightforward ways you can start writing about structure in your Songs of Ourselves analysis in order to satisfy the examiner These will help you build your confidence so you can develop your ideas and really impress.

Try...

thinking about the first and last lines of a poem from the Songs of Ourselves anthology. What has changed between them over the course of the poem and how do they convey this? Are they similar or a repetition, indicating circularity? Or do they show a shift in perspective?

Looking at the use of punctuation. We’ve mentioned caesuras above: how do these break down the poem’s structure

Visually looking at the shape of the poem on the page in the Songs of Ourselves anthology. Are all the stanzas the same length? Are they longer at the beginning, or at the end? Is there a sense of growth or diminishing in the poem that fits this shape?

Finding any significant rhymes: why has the poet chosen to create a connection between these two words? Or where does the poem’s rhyme scheme break down?

Thinking about why the poet has chosen to present the poet in that form. Why is the poet writing about love in a sonnet? Why have they decided to write in free verse, is the poem about freedom or restraint in any way?

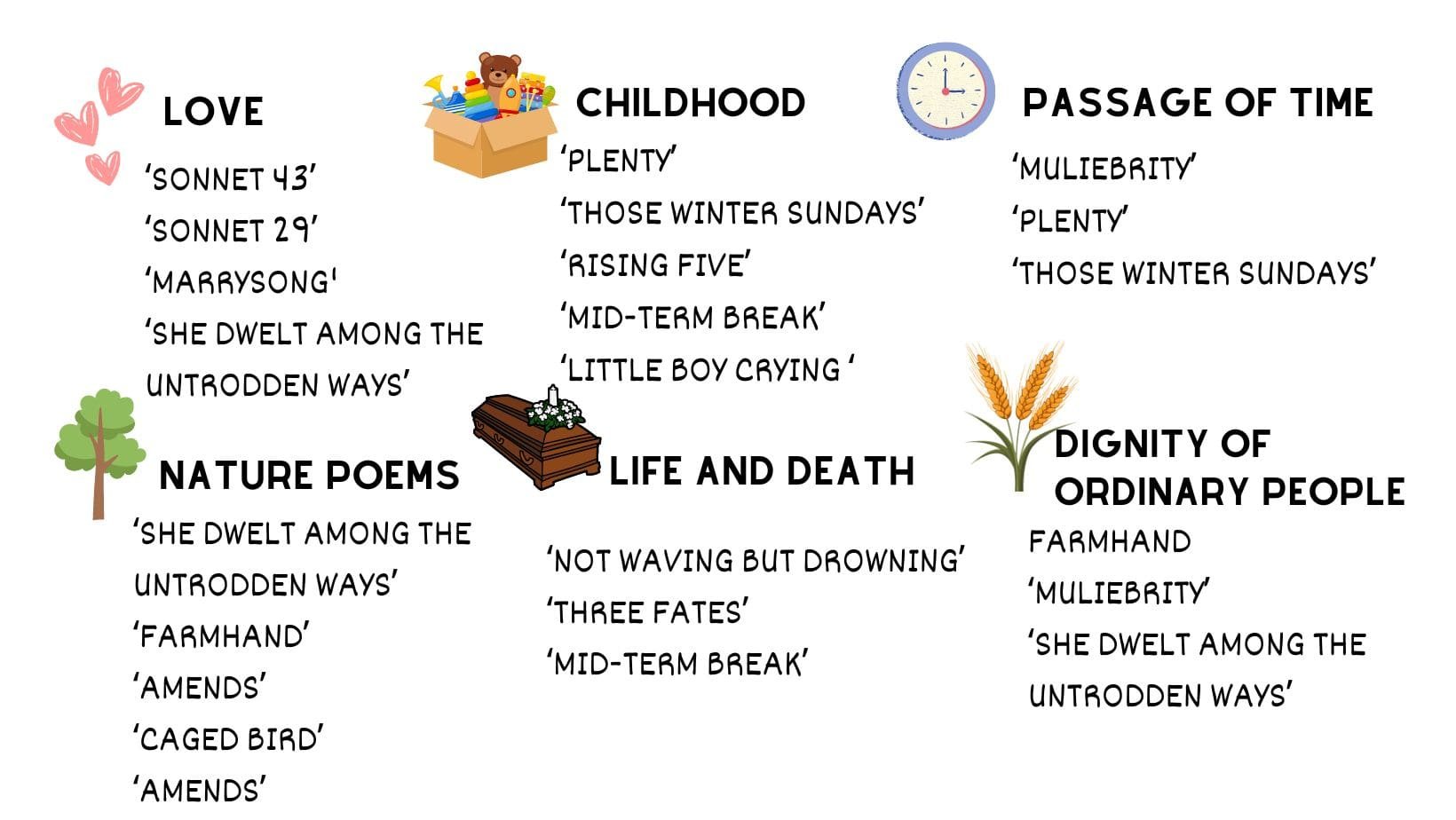

Thematic Approaches:

We’ve created this helpful graph so you can think about making more thematic links in your Songs of Ourselves analysis and strengthen your answer.

How to Make Notes on a Poem to Improve Songs of Ourselves Analysis

Here is an example set of notes on one poem from the Songs of Ourselves Collection:

‘Caged Bird’ (1983) by Maya Angelou (1928-2014)

Iconic African American poet, singer, memoirist, and civil rights activist. Broad career as a singer, dancer, actress, composer, and Hollywood’s first female black director, as well as working for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

Carol E. Neubauer recognised Angelou as “as a spokesperson for… all people who are committed to raising the moral standards of living in the United States.”

In 2010, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honour in the U.S., by President Barack Obama

The poem describes the contrasting experiences between two birds: one bird is able to live and fly free in nature as it pleases, while a caged bird suffers in captivity

The central contrast between the world of the free bird and that of the caged bird is sustained by the juxtaposition of the free bird treating the world like its own amusement park and the caged bird living trapped within a gothic ‘grave of dreams’, only able to mournfully sing of the freedom the other bird so ostentatiously enjoys

The free bird uses the entire natural world as its own dominion

In the first stanza, as in them all, rhymes and half-rhymes come quickly and often: the long open ‘ee’ of line 1’s “free” runs, assonant, through “leaps” and “stream” and the short ‘i’ of “wind” is carried through “still, “dips”, and “wing”, while “rays” assonates with “claims”

Alliterative patterns intensify the echoic richness: “bird” and “back”, “wind” and “wing”, “free” and “float”

There is also a run of “d” sounds linking the entirety of the stanza, from “bird” to “wind” and “ends”, culminating in “dares”

The combination of short lines, fast-running metre, and the sonic patterning creates a sense of energetic momentum and exhilaration

The second stanza begins with the conjunction “but”, and sets up the contrasts. Instead of the free bird’s flying movement through the “sun” and “sky” in the first stanza, the bird in the second stanza “stalks his narrow cage”, and can rarely “see”

The caged bird’s world is dark, like a grave, and the bird is itself reduced to insubstantial darkness, being only a “shadow”. “Shadow” implies a dark body, and the two birds symbolise racial segregation.

The use of the emotive verb “scream”, instead of a more conventionally avian noise such as “squawk” or “screech”, personifies the bird and underlines the human suffering represented by the caged bird

Grammatically, the caged bird is a passive subject of another agent—its wings are “clipped” and its feet are “tied”

Line emphatically repeated in fourth stanza: “His wings are clipped and his feet are tied/ So he opens his throat to sing”

Context: Abolitionist Frederick Douglass once said, “Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy”. Slave songs, Gospel, Blues, and jazz are all musical forms which have their roots in African American experience and black suffering

Though the bird’s song is of sorrow, it is still heard—the music will carry and find an audience, as it is “heard”, even on the “distant hill”.

Each stanza describing the free bird is followed by two stanzas describing the caged bird, demonstrating the emphasis of the analysis of black suffering

Despite the contrasts deployed to express racial segregation and injustice, there are some similarities between the caged bird and the free bird. Most obviously, the same animal is used a symbol for both blackness and whiteness, while stanza 1, describing the free bird, and stanza 2, describing the caged bird, are both sentence long, both visually similar on the page, and each have seven lines of up to six words or three beats, as well as each sharing irregular rhyme patterns. Correspondingly, stanzas 4 and 5, describing the free bird and caged bird respectively, are also similar—each has 4 lines and noticeably longer lines than the other stanzas. This may suggest an ultimate kinship, as well as demonstrating the intertwined worlds of the two worlds—they are not separate, but very much connected

Angelou’s image of the “caged bird” is borrowed from a poem by Paul Laurence Dunbar, “Sympathy,” which states, “I know why the caged bird sings, ah me […] / it is not a carol of joy or glee […]”

Autobiographical novel I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1984) vividly describes Angelou’s child and teenage years

Birds are associated with freedom and with singing, and thus with poets

In Angelou’s poem, the bird symbol in many ways universalises the situation, perhaps allowing readers/audiences in varying contexts of oppression and injustice to identify with it

In this sense, the poem speaks to anyone who is a victim of imbalanced power structures, and explores themes of freedom, oppression, nature, and black suffering

Songs of Ourselves Exam Questions

How does the poet create a profound feeling of nostalgia in this poem?

What feelings about nature does the poet convey in this poem?

How does the poet convey vivid impressions of the protagonist in these lines?

Explore how the poet’s writing so powerfully expresses a feeling of love in these lines

How does the poet present memory in the poem?

What feelings about memory does the poet convey in this poem?

Explore how Lindsay’s poem powerfully laments the loss of a lover.

How does the poet present the relationship between humanity and nature in this poem?

How do the poets vividly convey their feelings about love in these two poems?

How does the poet vividly convey their feelings about childhood in this poem?

Further Resources to Help Improve your Songs of Ourselves Analysis:

Helpful blogs:

Work with a GCSE English Tutor:

You may also find it helpful to work on an individual basis with a GCSE English tutor who is able to support you through handling the Songs of Ourselves poetry anthology and improving your Songs of Ourselves analysis for the GCSE exam. A GCSE English tutor can create personalised resources, supplementary resources such as Songs of Ourselves exam questions and model answers to help improve your Songs of Ourselves analysis. Get in touch now to book a free initial consultation and discuss how a GCSE English tutor can support you across all areas of your English GCSE.